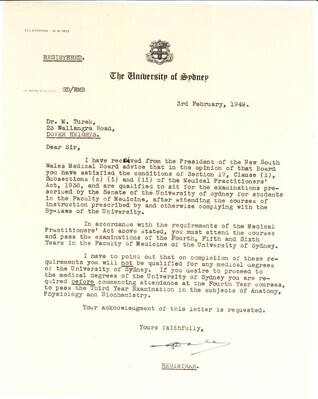

Object numberM2009/039:101

DescriptionRebuilding Professional Life: Letter from the Registrar of the University of Sydney confirming Dr. Michael Turek's admission into the fourth, fifth and sixth years in the Faculty of Medicine. After migrating to Australia in 1949, Dr. Turek had to endure three years of study at the University in Sydney in order to gain the necessary qualifications to practice in Australia. However, as stated in the letter, in completing his studies he was not entitled to receiving a medical degree from the University unless he sits for the third year examinations for Anatomy, Physiology and Biochemistry. Even though he was fully trained and had been working as a doctor in Poland for a number of years (most notably in the Bialystok ghetto hospital), he was still required to study if he wished to continue with his chosen profession. This letter demonstrates the processes through which many foreign doctors (fleeing their countries after World War II) had to undergo in order to qualify as doctors in Australia and be allowed to practice.

Dr Moses Turek was born 6 June 1908 in Tykocin, Poland, to the Jewish doctor Abraham Turek and his wife Sarah. In 1928, Moses began his medical studies in the Karlov Medical faculty, Prague. In 1931, Moses was accepted into Wilno University, within a strict quota of Jewish students. In 1935, while at Wilno hospital, Moses met and married Raya, a nurse. In 1936, their daughter Ada was born.

After the German and Russian Non-Aggression Pact, Tykocin became Russian occupied and Moses was placed in charge of the new community hospital. Meanwhile, his brother Isaac was arrested due to involvement with the local chamber of commerce and a Zionist organisation. Eventually, Isaac and his parents were deported to a camp in Siberia.

In June 1941, the Germans broke the Non-Aggression Agreement and once again Tykocin became German occupied. On 26 August 1941, all the Jews were ordered to assemble in the main square on the following Monday. Thinking that the Germans would shoot the men but not harm the women, Moses and his brother Menachem sought refuge at the house of a Polish friend.

Eventually they ended up in Bialystok, joined the Jewish community in the ghetto, and worked at the hospital. Hoping to find his family, Moses visited patients in the country side whenever he could. Mr Lupecki, a friend and former patient, visited Moses in the ghetto and devised a plan to sneak him and his brother out.

On 28 January 1943, they escaped by mingling with workers walking out the main gates. The Lupecki's hid them in their barn. But when Lupecki became head of production (of food and crops), the farm was no longer a safe hiding place. They moved to the Chojnacki farm: the owners in their 70s, the farm very rundown, welcomed their help and the two brothers had a small amount of money to help pay for their keep. The brothers moved many times between the Chojnacki's farm and other Poles who risked their lives to hide them.

On 11 August 1944, the Russians defeated the Germans in Tykocin. When Moses and Menachem learned that a Soviet artillery regiment had been stationed in Tykocin to guarantee the town's protection, they decided to go back home. Their father's house had survived so Moses moved in and began searching for his family. He received a card from Siberia, from his sister-in-law Malka Szymenczyk, advising him that his parents and brother were well. From another source, Moses learnt that his youngest brother Gregory, who had joined the British Army, had been killed. By 25 August 1944, Moses discovered that his wife Raya and daughter Ada, along with most of the Tykocin Jews ordered to assemble in the main square three years earlier, were massacred and buried in death pits in the forest.

In 1945 spring, the Jews of Tykocin decided to move to Bialystok to be part of a stronger community. The Polish pro-Soviet Government appointed Moses to organise medical services in the district hospital. He was awarded two medals, the Silver Cross of Merit and a bronze decoration for Victory and Freedom by the Polish Government.

Moses married Raya's sister Malka (as is custom in Jewish law) and a year later they had their first son, Gregory. For three years they stayed in Bialystok, but, eventually, the old prejudices drove the family to Australia. In 1949, they arrived in Sydney. Moses' Polish medical qualifications were not recognised so he retrained at the University of Sydney, studying for three years. In 1957, he renounced his Polish citizenship and become an Australian.

Dr Moses Turek was born 6 June 1908 in Tykocin, Poland, to the Jewish doctor Abraham Turek and his wife Sarah. In 1928, Moses began his medical studies in the Karlov Medical faculty, Prague. In 1931, Moses was accepted into Wilno University, within a strict quota of Jewish students. In 1935, while at Wilno hospital, Moses met and married Raya, a nurse. In 1936, their daughter Ada was born.

After the German and Russian Non-Aggression Pact, Tykocin became Russian occupied and Moses was placed in charge of the new community hospital. Meanwhile, his brother Isaac was arrested due to involvement with the local chamber of commerce and a Zionist organisation. Eventually, Isaac and his parents were deported to a camp in Siberia.

In June 1941, the Germans broke the Non-Aggression Agreement and once again Tykocin became German occupied. On 26 August 1941, all the Jews were ordered to assemble in the main square on the following Monday. Thinking that the Germans would shoot the men but not harm the women, Moses and his brother Menachem sought refuge at the house of a Polish friend.

Eventually they ended up in Bialystok, joined the Jewish community in the ghetto, and worked at the hospital. Hoping to find his family, Moses visited patients in the country side whenever he could. Mr Lupecki, a friend and former patient, visited Moses in the ghetto and devised a plan to sneak him and his brother out.

On 28 January 1943, they escaped by mingling with workers walking out the main gates. The Lupecki's hid them in their barn. But when Lupecki became head of production (of food and crops), the farm was no longer a safe hiding place. They moved to the Chojnacki farm: the owners in their 70s, the farm very rundown, welcomed their help and the two brothers had a small amount of money to help pay for their keep. The brothers moved many times between the Chojnacki's farm and other Poles who risked their lives to hide them.

On 11 August 1944, the Russians defeated the Germans in Tykocin. When Moses and Menachem learned that a Soviet artillery regiment had been stationed in Tykocin to guarantee the town's protection, they decided to go back home. Their father's house had survived so Moses moved in and began searching for his family. He received a card from Siberia, from his sister-in-law Malka Szymenczyk, advising him that his parents and brother were well. From another source, Moses learnt that his youngest brother Gregory, who had joined the British Army, had been killed. By 25 August 1944, Moses discovered that his wife Raya and daughter Ada, along with most of the Tykocin Jews ordered to assemble in the main square three years earlier, were massacred and buried in death pits in the forest.

In 1945 spring, the Jews of Tykocin decided to move to Bialystok to be part of a stronger community. The Polish pro-Soviet Government appointed Moses to organise medical services in the district hospital. He was awarded two medals, the Silver Cross of Merit and a bronze decoration for Victory and Freedom by the Polish Government.

Moses married Raya's sister Malka (as is custom in Jewish law) and a year later they had their first son, Gregory. For three years they stayed in Bialystok, but, eventually, the old prejudices drove the family to Australia. In 1949, they arrived in Sydney. Moses' Polish medical qualifications were not recognised so he retrained at the University of Sydney, studying for three years. In 1957, he renounced his Polish citizenship and become an Australian.

Production date 1949-02-03

Object nameletters

Materialpaper

Dimensions

- letter height: 262.00 mm

width: 206.00 mm

Credit lineSydney Jewish Museum Collection, Donated by Suzanne Binetter